How many 'I's does an 'I' make?

Neils Bohr, Kierkegaard, Reimann Surfaces, Atrial Fibrillation and 'Fortvivlelse'

J J Thomson believed that the atom is like a plum-pudding. The positively charged particles lie scattered with an equal number of negatively charged ones, the latter like raisins in the plum of positives. In came Ernest Rutherford, who with the help of Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, devised an ingenious experiment to improve upon it. They shot positively charged helium nuclei at a gold foil and watched what happened through a microscope. They observed that most of them just went straight ahead (point #1), some were slightly deflected, but a minority of them returned straight to where they came from (point #2). Rutherford was astonished. It took him a year to understand what was going on. He concluded, that the atom is mostly empty space (conclusion from #1) and there is a central positively charged nucleus which is tiny as compared to the rest of the atom (conclusion from #2). Bohr’s atomic model was born. But the negative electrons were a problem. How could these tiny ruffians remain in orbit if they all were negatively charged, he quipped to himself? They should repel each other, thus flying off helter-skelter destroying the skin (electron cloud) of the atom and its soul (the nucleus) with it.

Neils Bohr came to the rescue and the electrons were atributed with a style of their own. They were quantised, he said. They were not stupid negatively charged particles just flying around the nucleus like ruffians in a college circling their motor bikes around all Kareena Kapoor look alikes. The electrons had their own charm, chutzpah and canonised rules. They had their orbits which were ordained to them and they didn’t meddle with their fellow electrons or the nucleus unwittingly. Only if an exact amount of energy was given, would they shift their orbits, and they did so without emitting energy. No energy emitted means no die-hard action with the nucleus and the sanctity of the atom is maintained. They were like the biker dudes on Harley Davidson who travelled on country roads and city streets. If they saw an old lady trying to cross the road unaccompanied, they would all get off their bikes, and hand in hand help the lady along the zebra-crossing. Their creed was validated by unwritten rules of the biker ethos. So were the electrons in Bohr’s model. Self-respecting, self-sufficient, they wouldn’t budge with just any energy from their orbits, they would only shift across orbits if the exact energy was given, otherwise they minded their own business. They travelled on their aerial highways with ferocious speeds, troubling no one. Proud and courteous.

Neils Bohr thus solved the instability problem in Rutherford’s model of the atom. He single handily shifted the perspective from a strictly Newtonian application to the atomic world to a unique view, which placed the atom as an entity which didn’t necessarily follow all the rules of planetary scaled bodies.

I gave the above red carpet to Bohr for your consideration, gentle reader, so that you would appreciate his genius.

As a student and then as a mentor to other physicists, Bohr was famous for endlessly quoting from one his favourite fiction pieces, The Adventure of a Danish Student (1824) by Poul Martin Møller. The story is about a conversation between a graduate student, a licentiate, and a regular Joe, a philistine. While the licentiate is a man of exotic and abstract tastes of philosophical ramblings, the philistine is a traditional and practical God-fearing man.

In 1960, Bohr have a lecture titled "The Unity of Human Knowledge”, in which he quoted one of the philosophical discursions of the licentiate in the novel:

[I start] to think about my own thoughts of the situation in which I find myself. I even think that I think of it, and divide myself into an infinite retrogressive sequence of “I’s” who consider each other. I do not know at which “I” to stop as the actual, and in the moment I stop at one, there is indeed an “I” which stops at it. I become confused and feel a dizziness as if I were looking down into a bottomless abyss.

Bohr was an anxious fellow, always trying to perfect himself. He was a panicky and compulsive personality. Doubts would paralyse him and then he would doubt the doubt itself. He would enter into this regressive infinitude and in effect become stalled. There is a very common type of heart rhythm problem called atrial fibrillation in which all the parts of a heart chamber are beating in asynchrony. They are beating in such chaos and so fast that in toto they are pumping no blood at all. They become paralysed as a whole. Such was Bohr’s state when he was fighting his own demons.

Bohr was specially influenced by the philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard. Møller, while struggling to express the inner mind of a modern (19th century) soul through the duelling licentiate and philistine, was treading in the shoes of Kierkegaard, no less. Keirkegaard also struggled with the sense of infinite identities. In fact, it seems all Danes did (and perhaps still do). The Danish word for despair, Fortvivlelse, contains within it tvi, which means “two”. Tvivl means “doubt” and thus a despairing soul is a consciousness split into two. In effect, split infinitely. You can be torn in so many ways, you can’t make sense of who you are.

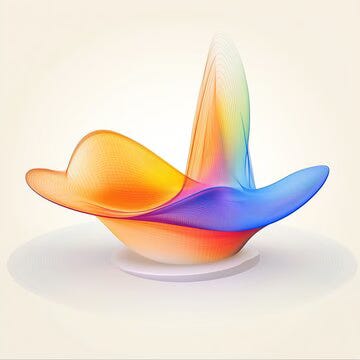

Bohr as a kid was surrounded by physicists, mathematicians and philosophers. He tried to find the answers to his troubled soul in mathematics. He came across Reimannian geometry. German mathematician Georg Reimann gave expression to what were known as multivalued functions, i.e. how functions (square root, cube root, logarithms, sines, cosine, etc) of complex variables could be represented geometrically as surfaces entwined with surfaces. They came to be known as Reimann surfaces. They are a beautiful way to represent functions. Bohr thought that the infinite splitting of our personality and egos could be thought of as there recurring enmeshed surfaces. As you go through life, you can keep peeling and discovering yourself.

I came across the above set of information in a book I am currently reading, The Making of the Atomic Bomb, by Richard Rhodes. While reading all this, a thought experiment occurred to me. May be you will like it too.

Imagine if I asked you to count from one through one thousand. By the time you are nearing the middle you will want the task to finish, but as you come closer to the end you will get a sense of relief. As one thousand is approaching, there is a finite length of time for which you have to exert mentally and physically. You feel your energy building up and your muscles relaxing. There is a chocolate at the end of one thousand.

Now, forget that you ever indulged in the above exercise. Instead, with a fresh mind, consider the task of counting to infinity with a chocolate at the end. The tension will only keep building. As you go farther and farther, a sense of dread will come over you. To hell with the chocolate. You will feel like slapping me and cursing yourself that you ever met a lunatic like me.

The “I’s” in you is perhaps like an infinite set of onion skins you will keep peeling throughout your life. The task is not to finish, you can’t after all. The idea is you ought to get comfortable with this dynamic act of discovering yourself while at the same time understanding the act has no end. Your “I” constitutes infinite Reimann surfaces waiting for you to unravel the whole you.

There is a line that Bohr was fond of quoting from the poet Friedrich Schiller:

Only wholeness leads to clarity,

And truth lies in the abyss

Thank you for reading.